The men on the panel come from all walks of life: a former police chief, an ex-offender, and an advocate for newly released prisoners. Each speaker dives into his personal story and experiences, sometimes punctuating comments with a national statistic on incarceration. Different journeys converging to address a single issue: ex-offender reentry.

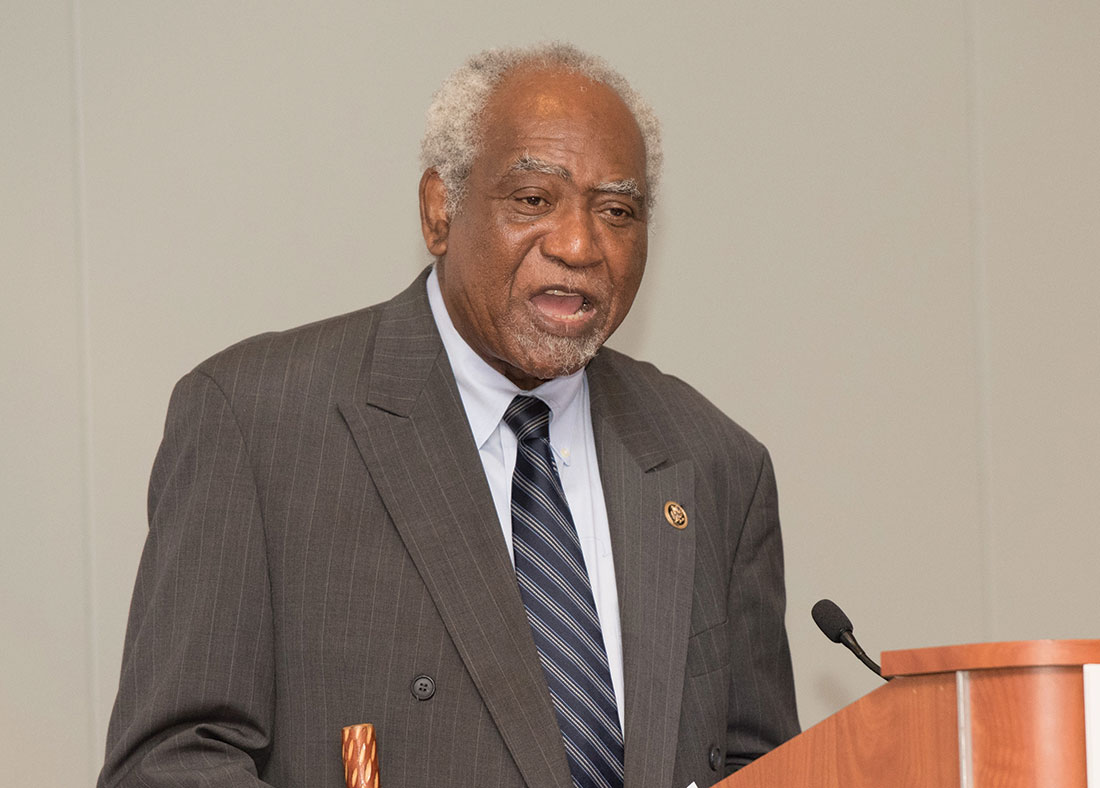

“We’re going to look at the problem,” said Rep. Danny Davis (D-Ill.) in opening remarks of the session on ex-offenders and reentry. “Many of us don’t know there are 70 million people in this country with records.”

This 2016 forum, hosted by Davis during the Congressional Black Caucus Foundation’s 46th Annual Legislative Conference, examined programs and initiatives that are helping fathers and other returning citizens successfully transition back into the community and rejoin their families. These are important issues that must be addressed, Davis said, not only because having a criminal record oftentimes negatively impacts employability, but also weakens the black family structure.

The congressman explained that there are children who grow up without the opportunity to see – or know – their fathers. “I don’t know a single black family that is not impacted by this issue of reentry,” Davis added.

Framework of Family

Daryl Atkinson knows both sides of the coin. As the Second Chance fellow for the Department of Justice, Atkinson said the DOJ’s work around reentry falls into three categories: policy, grantmaking programs and “bully pulpit,” a position of authority from which to advocate or influence public issues. But before delving into the agency’s initiatives, he stressed the importance of building the discussion around the “overarching framework of family.”

“How should we think about our people returning home? Because that’s what they are, they are people,” said Atkinson, who smacked down common identifiers like ex-offenders, felons and convicts. “They are members of our community, they are members of our family.”

The dialogue resonated with Atkinson for another reason, too. In 1996, he was convicted of a first time nonviolent drug crime and sentenced to 10 years in prison. Atkinson said he served a mandatory 40 months on that sentence before being released in 1999. On Nov. 4 of that year, his parents rented a Lincoln Town Car and picked him up from a maximum-security prison where “60 percent of the population had life without parole.”

Years later, he would ask why they rented such a fancy car on the day of his release. The simple answer: “To show you that period in life didn’t completely define you, and we have a set of expectations for you now that you’ve returned home.” With that family culture of support, Atkinson has gone on to earn a series of academic degrees (from associate’s to Juris Doctor), is licensed to practice law in Minnesota and North Carolina, and has been honored by the White House as a “Champion of Change” in removing barriers for people with criminal records.

“The only thing that separated me from them is that I had that loving support system and an environment where I could succeed,” he told the audience.

Similarly, DOJ is also pushing initiatives to support the success of those transitioning back into their communities. The Bureau of Justice Assistance has issued more than “700 grants totaling over half a billion dollars” to reentry service providers nationwide for transitional services like housing, job training, food and shelter, said Atkinson. On the policy front, the Office of Personnel Management has proposed a rule to “ban the box” for federal employment, giving people with records a “fair opportunity” to get a job.

The Department of Education initiated a Pell Grant program for incarcerated persons, opening up access to post-secondary education with the goal of being a life-changer for these individuals. And the Department of Housing and Urban Development, added Atkinson, has issued guidance to housing providers that “using criminal record history as an automatic barrier to rent or buy a home can run afoul of the Fair Housing Act and be deemed as racial discrimination.”

‘Engagement Over Enforcement’

Federal agencies aren’t alone in working to close the opportunity gap. In Cincinnati, Ohio, Jeffrey Blackwell implemented reentry initiatives that he said positively impacted the community. The former Cincinnati police chief stressed community engagement over locking up people. “I believe in engagement over enforcement, and lifting up communities,” said Blackwell, later adding, “Policing needs a tune-up – I’m just being nice, the engine’s blown and it needs to be replaced.”

Under his leadership, the Cincinnati police department started programs like “Right to Read,” putting officers full time in elementary schools to teach third graders how to read. “Why not interrupt the cradle to prison pipeline by helping these young brothers and sisters pass that test?” he asked. His leadership style, however, didn’t go unchallenged. He was fired from that position in 2015.

Meanwhile, Albert “AL” Long, vice president of the Juvenile Justice Division for Correctional Management & Communications Group, also in Cincinnati, has adopted a “creative” approach to helping those reluctant to change. It’s a three-week program structured like a “professional bootcamp” that he believes can be used by correctional institutions and halfway houses. “There is no option for failure,” he stressed.

The program emphasizes networking, self-awareness and conflict resolution. Community partnerships are key to these individuals transitioning into the workforce, with partners providing interview-appropriate attire like suits and dresses, and rigorous job interview prep.

Fatherhood First

For Halbert Sullivan, changing the mindset is the first step in changing lives. “If a person isn’t ready,he may pretend, but he’s not going to do too much,” said Sullivan, himself a recovering drug addict with multiple stints behind bars. When ready, he made a life change and went on to earn a master’s degree.

As the CEO of the Fathers’ Support Center in St. Louis, Mo., he strives to reconnect black fathers to their families and communities. The goal of the organization he founded in 1997 is to get fathers involved – and employed – to alter the “trajectory” of their children. Sullivan cited statistics indicating that in homes with absent fathers, children are more likely to use drugs, drop out of high school, and become juvenile offenders. He said teenage girls are more likely to get pregnant and continue the cycle. But a challenge for many of these fathers: a background with felonies. It’s a reason reentry work became a key component of outreach.

“We work with a project in the penitentiary where we go in and provide parenting and other relationship skills building,” explained Sullivan. “But we also take a family therapist in so we can begin to reconnect [fathers to their families],” particularly the kids.

All reentry programs include vocational skills training. “The main goal at the end of the day,” said Sullivan, “is employment.”

The Big Picture

The panelists laid out programs aimed at making a positive impact on the lives, communities and people they have served. Their storied paths have taken them to the front lines of the reentry discussion, including bringing them to this year’s forum helmed by Davis. “I have a lot of respect for people who take the tough challenges,” Davis said during the two-hour panel.

Observers might argue Davis is one of those people. As a longtime champion of legislation to help ex-offenders, he spearheaded the Second Chance Act. It aimed to reduce recidivism by boosting resources for transitional services available to the formerly incarcerated. With the millions of people in this country with records, according to Davis, reentry issues are increasingly on the radar of leadership and policymakers at the state-level.

“We are indeed making progress with this issue,” said Davis, but there is more to be done to whittle down the numbers.